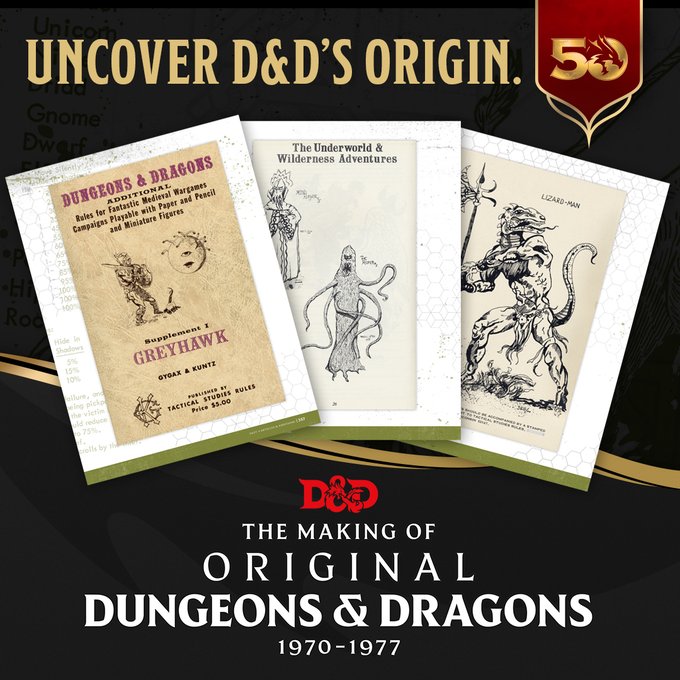

It's not surprising that Wizards' releases for 2024 largely center around the 50th anniversary of Dungeons & Dragons. In Vecna: Eve of Ruin, Wizards' goal was the biggest adventure 5E has seen, with one of the game's oldest villains. With The Making of Original Dungeons & Dragons: 1970-1977, Wizards is going back to the roots of the game, presenting material other histories have not.

“There are a lot of books that tell people how D&D was made, but [what] we wanted to do with this was show it to you instead,” said senior game designer Jason Tondro. “So what this book does is... it includes everything from before D&D existed. Games were being made that influenced D&D, and then the first draft of D&D that Gary Gygax typed out in Lake Geneva, then the first printing of the Brown Box, the first version of D&D that ever hit the world.”

“And all of this, all this stuff,” Tondro continued, “is interspersed with letters and correspondence between Dave [Arneson] and Gary, or all kinds of ephemera and unusual documents from the period. So you get this overall historical view where you can see the materials that were being created that went into Dungeons & Dragons, and you can see the game being evolved and come to creation. And then you can see how it changed and it altered in the years leading up to Advanced Dungeons & Dragons.”

“This is what really makes this book different from every other history of D&D book. It's not a history. This is the making of original Dungeons & Dragons. You get to see the game being made in front of your eyes,” said Tondro.

To do that, the book is big – so big that they joked about using it for exercise during the press preview. At 576 pages, it's even bigger than Dungeons & Dragons: Lore & Legends, which is 416 pages.

The book is divided into four sections, each of which has its own color-coded ribbon. Part 1 is about the precursors to D&D. Part 2 focuses on the 1973 draft of D&D. Part 3 is about Original Dungeons & Dragons, looking at the draft version versus the published one, the Brown Box and White Box. Part 4 is “Articles & Additions,” including Greyhawk, Blackmoor, Eldritch Wizardry, and The Dragon, among others.

“Having worked on books like Playing at the World, The Elusive Shift, Game Wizards, and so on, and I have looked through multiple admirations [sic] of kind of how D&D came together,” said Peterson, “and I thought, wouldn't it just be amazing to be able to go back to all the originals? Unfortunately, some of the material that tells the story, it's kind of hard to get these days.”

Not only does the fact that 50 years has passed since D&D was created present a challenge for historians. Availability and condition are also key factors.

A lot of these fanzines were printed in absolutely minuscule numbers,” said Peterson. “They now command prodigious sums at auction, and getting access to some of the even more detailed, kind of in-house development documents is perhaps even more difficult still. And so really, just having the opportunity to put those tools out there in front of people, and to be able to say, D&D has this conceptual history.”

The book has a wealth of documentation from club newsletters and the like that show how OD&D evolved and changed. They're also hard to read at times as materials aged and faded. The team did their best to present those documents as they exist. However, because of the initial poor quality and how time and storage affected them, some clean up was necessary in a few places. Overall though, documents are presented as they were found, even if it makes certain words hard to read here and there.

Another thing of note in some of these early documents is off-color language and language that would not be used today. They didn't change it because it's history. They did, however, placing it in historical context, so the readers can read it for themselves and decide what they think of it. For example, there is a parenthetical comment on one page from around 1973/1974 that's a dig at the women's lib movement (ED: not pictured). It's still there in the reproduction of the page.

“A real focus of my own work has been showing that D&D didn't happen in a vacuum, right?” said Peterson. There were cultural conditions, there were sociological interactions that were kind of necessary... For me, this book would be twice as long. We'd be talking about [a] 1,200 page version of this. But, you know, we did our best to be able to include what we could that we thought was kind of the most essential to telling the story.”

Before D&D, there was Braunstein. During the press conference, however, Tondro mistakenly referred to it as “Brownstein”, which is corrected where appropriate.

“Braunstein is a fascinating and often forgotten element of the evolution of D&D,” said Tondro. “It's a kind of war game. It was developed by a fellow named David Wesely, who's still running these games, by the way. He was running them at GaryCon just a few months ago. Braunstein was a war game of Napoleonic armies invading this little Austrian town, but what made it unusual is that the players were assigned characters in town, and Dave Arneson, for example, was assigned the role of a student. And they had their own sort of side objectives that they could pursue [and] that they could still win even if Napoleon conquered the town. And this idea, what made it unusual, was that the players could kind of try anything like the players playing the student could try any kind of risk or gamble that they could think of and then the referee had to think up an impromptu kind of 'what happens next' consequence and how does that work, and you know, does your strategy succeed?”

Tondro continued, “This was really unusual and the players in this Twin Cities gaming club. They loved it, and they continue to innovate and iterate on this idea. They ran a Western version of this called 'Brownstone,' in which Dave Arneson played a bandit named 'El Pancho,' and then Arneson decides to create his own, what he called 'medieval Braunstein,' and that's what you're looking at right here is the announcement in his newsletter than his medieval Braunstein is gonna be starting, and this “Braunstein” became “Blackmoor.”

Arneson's zine was called “Corner of the Table” and went out to his local group as well as to people in other cities, including Gygax in Lake Geneva. It shows how much of a hobby this was. It was all done so casually with no thought that this could evolve into something like what the RPG industry and what D&D has been like in the 50 years that followed.

“Gygax was a great recycler and developer of ideas. I wouldn't describe him 'an idea man.'” said Peterson. “He was someone who kind of would pull from all these different sources and put things together. There's a fellow named Jeff Perren who had developed some mass combat medieval rules, and Gary kind of borrowed those.” Peterson

“Yeah, Arneson was the idea man,” agreed Tondro.

“Gary did his work in public. I mean, his greatest talent perhaps was that he was a consensus builder. He was someone who found clubs, got people organized, socialized rule, and he worked best interacting with other people's proposals. That's what really got him fired up, is seeing somebody else has a way of doing this. 'I could turn that into a system that would have like this quality and this quality and it would be really cool, and ultimately even something we might be able to turn into a product and sell 'em.” Peterson explained. “I would say ultimately Arneson was perhaps a bit more ambivalent overall about the prospects of commercializing a hobby,” Peterson added.

And before there was a D&D, Arneson and Gygax collaborated on a game called Don't Give Up the Ship, which was released by Guidon Games. However, Guidon Games didn't pay Arneson anything for it, which made Arneson swear he'd never submit anything else to them again, but Gygax did, and Guidon Games rejected it, setting the stage for them to do it themselves.

Tondro discovered that Arneson is the one who said, there has to be a better way to handle damage in combat and added hit dice. Arneson loved the drama and uncertainty of meeting an ogre and not knowing how much it would take to beat it because it wasn't a static number. The book also documents the work of Leonard Pat, who is a name the average D&D player won't recognize yet contributed to the evolution of the game.

“Leonard Pat had produced a set of rules in 1970 that Gary Gygax effectively cribbed from,” said Peterson. “These are rules that had wizards and anti-heroes and heroes and dragons. It was very Tolkien scoped, which is not as true of Chainmail. You see a lot of elements in Chainmail that go against the way Middle Earth actually was structured, and Gary complained all the time about people telling him that Chainmail was wrong because it wasn't faithful to Tolkien.... The evidence is overwhelming from my perspective that that was an article that was known to the creators of Chainmail, but this was again who Gary was. He would see something like this two-page set of rules that Leonard Pat put in a fanzine late in 1970 and be like, 'oh my god, I can take this and build it out into, you know, this much larger thing and it'll add more monsters, will add more spells, and we'll kind of build this whole thing out of that. All the best things he [Gary] did, he did in reaction to something like that.”

“There's no hidden dungeon, right? And there's no collaboration in the parties, and, you know, combat systems in it are fairly rudimentary... You get to a room and Monopoly-style, you're drawing a card, like from the community chest to determine what it is going to happen when you get there. So it's not strictly speaking an adventure like we would understand a module now,” said Peterson.

“Dungeon feels to me more like an ancestor of games like Talisman and Hero Quest than it is of adventure modules,” added Tondro.

TMoOD&D ends with the realization that a new edition of D&D will be needed, the edition that will become Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. And the rest, as they say, is history.

The Making of Original Dungeons & Dragons: 1970-1977 does not have an early release date. It will be available for purchase on June 18 for $99.99.

“There are a lot of books that tell people how D&D was made, but [what] we wanted to do with this was show it to you instead,” said senior game designer Jason Tondro. “So what this book does is... it includes everything from before D&D existed. Games were being made that influenced D&D, and then the first draft of D&D that Gary Gygax typed out in Lake Geneva, then the first printing of the Brown Box, the first version of D&D that ever hit the world.”

“And all of this, all this stuff,” Tondro continued, “is interspersed with letters and correspondence between Dave [Arneson] and Gary, or all kinds of ephemera and unusual documents from the period. So you get this overall historical view where you can see the materials that were being created that went into Dungeons & Dragons, and you can see the game being evolved and come to creation. And then you can see how it changed and it altered in the years leading up to Advanced Dungeons & Dragons.”

“This is what really makes this book different from every other history of D&D book. It's not a history. This is the making of original Dungeons & Dragons. You get to see the game being made in front of your eyes,” said Tondro.

To do that, the book is big – so big that they joked about using it for exercise during the press preview. At 576 pages, it's even bigger than Dungeons & Dragons: Lore & Legends, which is 416 pages.

The book is divided into four sections, each of which has its own color-coded ribbon. Part 1 is about the precursors to D&D. Part 2 focuses on the 1973 draft of D&D. Part 3 is about Original Dungeons & Dragons, looking at the draft version versus the published one, the Brown Box and White Box. Part 4 is “Articles & Additions,” including Greyhawk, Blackmoor, Eldritch Wizardry, and The Dragon, among others.

Digging Into Historic Documents

Working with Tondro and the D&D team on this massive work is D&D historian Jon Peterson. Wizards reached out to Peterson in 2021, asking if he had any ideas for a look at D&D's history that hadn't been sufficiently addressed.“Having worked on books like Playing at the World, The Elusive Shift, Game Wizards, and so on, and I have looked through multiple admirations [sic] of kind of how D&D came together,” said Peterson, “and I thought, wouldn't it just be amazing to be able to go back to all the originals? Unfortunately, some of the material that tells the story, it's kind of hard to get these days.”

Not only does the fact that 50 years has passed since D&D was created present a challenge for historians. Availability and condition are also key factors.

A lot of these fanzines were printed in absolutely minuscule numbers,” said Peterson. “They now command prodigious sums at auction, and getting access to some of the even more detailed, kind of in-house development documents is perhaps even more difficult still. And so really, just having the opportunity to put those tools out there in front of people, and to be able to say, D&D has this conceptual history.”

The book has a wealth of documentation from club newsletters and the like that show how OD&D evolved and changed. They're also hard to read at times as materials aged and faded. The team did their best to present those documents as they exist. However, because of the initial poor quality and how time and storage affected them, some clean up was necessary in a few places. Overall though, documents are presented as they were found, even if it makes certain words hard to read here and there.

Another thing of note in some of these early documents is off-color language and language that would not be used today. They didn't change it because it's history. They did, however, placing it in historical context, so the readers can read it for themselves and decide what they think of it. For example, there is a parenthetical comment on one page from around 1973/1974 that's a dig at the women's lib movement (ED: not pictured). It's still there in the reproduction of the page.

The Precursors to D&D

D&D did not spring fully formed from the mind of Gary Gygax. TMoOD&D starts with significant look at the forces and influences that led to the game we know.“A real focus of my own work has been showing that D&D didn't happen in a vacuum, right?” said Peterson. There were cultural conditions, there were sociological interactions that were kind of necessary... For me, this book would be twice as long. We'd be talking about [a] 1,200 page version of this. But, you know, we did our best to be able to include what we could that we thought was kind of the most essential to telling the story.”

Before D&D, there was Braunstein. During the press conference, however, Tondro mistakenly referred to it as “Brownstein”, which is corrected where appropriate.

“Braunstein is a fascinating and often forgotten element of the evolution of D&D,” said Tondro. “It's a kind of war game. It was developed by a fellow named David Wesely, who's still running these games, by the way. He was running them at GaryCon just a few months ago. Braunstein was a war game of Napoleonic armies invading this little Austrian town, but what made it unusual is that the players were assigned characters in town, and Dave Arneson, for example, was assigned the role of a student. And they had their own sort of side objectives that they could pursue [and] that they could still win even if Napoleon conquered the town. And this idea, what made it unusual, was that the players could kind of try anything like the players playing the student could try any kind of risk or gamble that they could think of and then the referee had to think up an impromptu kind of 'what happens next' consequence and how does that work, and you know, does your strategy succeed?”

Tondro continued, “This was really unusual and the players in this Twin Cities gaming club. They loved it, and they continue to innovate and iterate on this idea. They ran a Western version of this called 'Brownstone,' in which Dave Arneson played a bandit named 'El Pancho,' and then Arneson decides to create his own, what he called 'medieval Braunstein,' and that's what you're looking at right here is the announcement in his newsletter than his medieval Braunstein is gonna be starting, and this “Braunstein” became “Blackmoor.”

Arneson's zine was called “Corner of the Table” and went out to his local group as well as to people in other cities, including Gygax in Lake Geneva. It shows how much of a hobby this was. It was all done so casually with no thought that this could evolve into something like what the RPG industry and what D&D has been like in the 50 years that followed.

Chainmail

TMoOD&D includes the second printing of Chainmail, which contains terms still used in the D&D today. Both versions of Chainmail had ideas Gygax encountered elsewhere.“Gygax was a great recycler and developer of ideas. I wouldn't describe him 'an idea man.'” said Peterson. “He was someone who kind of would pull from all these different sources and put things together. There's a fellow named Jeff Perren who had developed some mass combat medieval rules, and Gary kind of borrowed those.” Peterson

“Yeah, Arneson was the idea man,” agreed Tondro.

“Gary did his work in public. I mean, his greatest talent perhaps was that he was a consensus builder. He was someone who found clubs, got people organized, socialized rule, and he worked best interacting with other people's proposals. That's what really got him fired up, is seeing somebody else has a way of doing this. 'I could turn that into a system that would have like this quality and this quality and it would be really cool, and ultimately even something we might be able to turn into a product and sell 'em.” Peterson explained. “I would say ultimately Arneson was perhaps a bit more ambivalent overall about the prospects of commercializing a hobby,” Peterson added.

And before there was a D&D, Arneson and Gygax collaborated on a game called Don't Give Up the Ship, which was released by Guidon Games. However, Guidon Games didn't pay Arneson anything for it, which made Arneson swear he'd never submit anything else to them again, but Gygax did, and Guidon Games rejected it, setting the stage for them to do it themselves.

Giving Contributors Their Due

Research for this book brought home for Tondro how much of an impact Arneson had. He knew the name, but not what he did, especially since Tondro began playing after the Chainmail days. Gygax had plans for a third edition of Chainmail but in the meantime had been reading Arneson's zine. Blackmoor brought the concept of hit dice.Tondro discovered that Arneson is the one who said, there has to be a better way to handle damage in combat and added hit dice. Arneson loved the drama and uncertainty of meeting an ogre and not knowing how much it would take to beat it because it wasn't a static number. The book also documents the work of Leonard Pat, who is a name the average D&D player won't recognize yet contributed to the evolution of the game.

“Leonard Pat had produced a set of rules in 1970 that Gary Gygax effectively cribbed from,” said Peterson. “These are rules that had wizards and anti-heroes and heroes and dragons. It was very Tolkien scoped, which is not as true of Chainmail. You see a lot of elements in Chainmail that go against the way Middle Earth actually was structured, and Gary complained all the time about people telling him that Chainmail was wrong because it wasn't faithful to Tolkien.... The evidence is overwhelming from my perspective that that was an article that was known to the creators of Chainmail, but this was again who Gary was. He would see something like this two-page set of rules that Leonard Pat put in a fanzine late in 1970 and be like, 'oh my god, I can take this and build it out into, you know, this much larger thing and it'll add more monsters, will add more spells, and we'll kind of build this whole thing out of that. All the best things he [Gary] did, he did in reaction to something like that.”

The Dungeon

Before Dungeons & Dragons the RPG, there was Dungeon the game, and it's less the role-playing game we know today or a module than something Peterson describes as similar to the ancillary board games D&D has put out over the years that approximate play.“There's no hidden dungeon, right? And there's no collaboration in the parties, and, you know, combat systems in it are fairly rudimentary... You get to a room and Monopoly-style, you're drawing a card, like from the community chest to determine what it is going to happen when you get there. So it's not strictly speaking an adventure like we would understand a module now,” said Peterson.

“Dungeon feels to me more like an ancestor of games like Talisman and Hero Quest than it is of adventure modules,” added Tondro.

TMoOD&D ends with the realization that a new edition of D&D will be needed, the edition that will become Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. And the rest, as they say, is history.

The Making of Original Dungeons & Dragons: 1970-1977 does not have an early release date. It will be available for purchase on June 18 for $99.99.